Hi I am Cory Flemings from abco automation and welcome back to Whiteboard Insights. Today I want to tell you a story about a discussion I had recently about cubic velocity.

It goes kind of like this. Back in the history of man we created the distribution center design and before there were computers we basically had static locations and somebody walked through a warehouse and getting stuff off the shelves. And that is how we got to this world of distribution center design. Many of us are still thinking in those days when we talk about the Pareto curve. We all know and love the Pareto curve, it’s on our logo, and we love the Pareto curve.

It tells us a lot about the way an operation works. We all know that 20% of SKUs to 80% of the business but we usually measure things in order lines and the reason we have historic play or traditionally talked about order lines is because it has to do with how many times we go and visit a pick location during the day. It was born in the world where all the SKUs have static pick faces. Then it really matters about order lines. If I have one product that does 100 order lines a day and that means we have to go to that pick face 100 times.

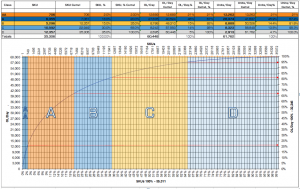

But now things are different now we work with computers and automated technologies and so forth the world has changed and the world has changed and this one remarkable way we are no longer concerned with order lines per day we are concerned with cubic velocity. What is cubic velocity?

Well as you can see from my board cubic velocity is the number of pieces you sell a day of a particular SKU times its piece cubed. So if I have a lamp, as an example, a lamp might come in a box this tall and this big but I sell 25 lamps a day you can understand the cubic velocity of this product might be a pallet load a day. I am moving up a pallet load of this product everyday

On the other hand if I talk about pencils, straight pens or chopsticks or things that are small and thin I can put 2000 of those things in a tub and if I’m moving 2000 lines a day I can manage that much the volume with one tub of that product. And so the difference in cubic velocity is immense.

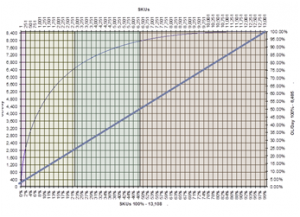

So the person and I were having this conversation they said, “I don’t understand why you’re putting lamps in a pallet flow line that doesn’t make sense”.

I said, “That’s because you’re still thinking in terms of lines, it only does 25 lines a day, but you are moving a pallet load of stuff through your warehouse every day when you sell these lamps. Over here you’re right to have these small items, these trinkets, that you move a lot more lines but you only move one tub of day.”

So for distribution center design in an automated system I am concerned with how much stuff you have to move around a system, even in a manual system that is completely manual think about how much cube you have to move through your building every day. Some products you have to vote the entire pallet, other products you don’t.

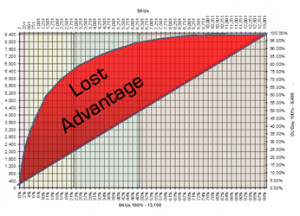

In fact think of your carton flow racks today and how much how many of them have backstock on the backside of the flow rack and I will bet you the reason is you haven’t thought of cubic velocity you are thinking of lines that product moves a certain number of lines a day but the cubic velocity drips out the back of the flow rack sits on the floor.

I encourage you to think about cubic velocity in your distribution center design and if you would like us to give you a hand we would be happy to help you out go to www.abcoautomation.US and connect with us we would be happy to give you a hand.

Sound Interesting? Contact us today and let’s see how we can work together to make your distribution center great.