The picking process is a fundamental role in warehouse and distribution practices.

The picking process is a fundamental role in warehouse and distribution practices.

Do You Have Pickers or Walkers in Your Distribution Center?

Is Just in time Distribution a Solution for your Supply Chain?

A recent development in the supply chain is just in time distribution, also known as JIT. While there are certainly some risks to just-in-time distribution, there are also substantial rewards if you can execute it properly. So, first of all what is just-in-time distribution? It is fairly simple; it is exactly what it sounds like. It is getting the product in front of the customer right when you need to, whether that is in a retail outlet or online.

Let’s delve a little deeper into how just in time distribution can be best used to optimize your supply chain.

Lower Store Footprint: A lot of the cost in retail is the overhead of the store building itself. Now, if you can reduce the footprint, and still have the capability to sell as much, this is a big win for you. If you don’t need an enormous back stock (or any back stock for that matter), you can reduce the footprint of your store, decreasing your rent and utilities spend. The Europeans are very good at this, and pharmaceutical wholesalers caught on very quickly by increasing their service offerings. Some German wholesalers deliver to their customers eight times a day! This just-in-time service allows the pharma retailer to make his entire footprint retail space, and allows him to reduce the shelf space assigned to each SKU resulting in more SKU facings, and more product availability. Of course, the wholesaler has to really be on his toes!

Fresher Product: Not necessarily just for food, but for any perishable items. JIT distribution can make sure you aren’t paying for goods that you don’t need right now, and might never need. Or even worse, a product that might expire before you can get them out to your customers to even have a chance to sell them.

So here is what that means for your supply chain:

Bigger, more-responsive DC: If you have little or no back stock in your stores than you will need more space in your DC. You have to store the product somewhere, correct?

However, if you have read our previous blogs, you know that the most efficient way to store and pick items is not in a huge DC. You need more space, but not necessarily space on the floor. Use the cubic space in the air. You pay for the ground; the air is free. This means using an automated system and product-to-person distribution, especially for your slower moving items.

By maintaining more inventory in the distribution center, you get the added benefit of buying items at a better price point in bulk, and storing them in a less-expensive DC. You can also buffer all of your shipments there while having them ready to go to the stores when needed, or JIT.

The challenge is getting product to the store at exactly the right time.

In the scenario above you might consider contracting with a large shipper FedEx or UPS to ensure that you get guaranteed shipping to all of your destinations in time for your customers to buy. The other option is have a lot of decentralized, smaller distribution centers located around the service areas where you distribute. You can control timing of shipments to your customers better with shorter transportation runs and a decentralized distribution center; however you incur more cost.

JIT is a rather delicate process. But if you have the advantage of working with a partner who can help you maximize the efficiencies and minimize the risk, JIT can be a great solution for your supply chain. You will need analyses of how your supply chain is set up, current operations, your order profile and customer base; a lot of different variables go into seeing if you can do JIT.

When you work with a system integrator that can take an analytical and mathematical approach to distribution, you can take more advantage of having a JIT supply chain. Considering Just in Time distribution in your supply chain might make a lot of sense.

Click here to request to speak with abco about how Just-in-time Distribution might be able to help your supply chain?

5 Reasons to Choose a System Integrator for Your DC Project

So why should you use a system integrator instead of a manufacturer for your distribution center project? After all, a manufacturer knows the product best and will be able to give you the best price too, right?

Well, not always.

The main reason a system integrator is the best partner for your distribution center is their ability to choose. Integrators have flexibility to choose from different suppliers that will work best for you. This is opposed to a manufacturer trying to shoehorn a solution with one of the products they make.

Let’s explore these advantages:

Efficiency: Whether defined by cost or performance, system integrators can source the most efficient components for your application. Not all of the technologies that would yield the most efficient solution can be sourced from the same manufacturer. But why can’t manufacturers just integrate different technologies?

Bias: Even if some manufacturers say that they are free to use any competitor’s components, what are they more likely to push you towards? One of theirs, right? And who can blame them? They know the technology better; they make more money, and lower their risk by pushing something they make vs. buying it from a competitor. Which leads us to…

Competition: Manufacturers are less inclined to use a competitor’s technology. Obviously manufacturers are not in the business of helping their competitors by integrating their technology solutions; they are in the business of selling their own. System integrators, on the other hand, are not constrained in their choice of vendors since they aren’t really competing with the manufactures; the manufacturers are their suppliers.

Cost: Just because one manufacturer makes one component cheaper doesn’t mean that all their components are the best value. If manufacturer A makes an inexpensive #1 and #2 component, but #3 is expensive, and manufacturer B makes an inexpensive #3 and #4 but everything else costly, doesn’t it make sense to mix and match and save money? That’s where a system integrator help you can lower your aggregate system cost.

Experience: A good system integrator has a variety of experience with different technologies. Instead of being a manufacturer that has one set of solutions, a system integrator can have both the access to, and experience with a variety of technologies.

So what do you see as the best reasons to work with a distribution center system integrator vs. a manufacturer? Let us know by commenting below. And if you would like to talk to a system integrator about your distribution center project contact abco automation.

ROI from Your Automated Distribution Center

When designing an automated distribution center the ROI of your design is one of the most important factors. ROI is a function of three things: capital, labor and building space.

When designing an automated distribution center the ROI of your design is one of the most important factors. ROI is a function of three things: capital, labor and building space.

No matter how you cut it, all three are always in tension: you can have a low labor headcount and a small footprint, but you will have high capital costs. You can have a lower capital cost and a low building footprint, but you will have a higher headcount (two shifts instead of one). You can have a low capital cost, but you will trade with an increase in labor and footprint.

Let’s expand on the topic and look at your options when you focus on each individual component.

Conserve Capital: Most traditional distribution centers in the US focus on this. This is where you lease or build a 30 foot high DC. There is usually a great deal of static racking and conveyor and very little automation.

Effect on Labor: There will be high labor rates. With little advanced technology you can’t perform product-to–person picking. To generate more throughput you have to have more people. Limited technology can be used, but it will along the lines of pick-to-voice.

Effect on Space: When you conserve capital and don’t spend on more advanced technology you typically end up with a low building with a big footprint. This usually means you are further away from a desirable transportation trunk. If you try to limit the footprint you end up spending on more labor from having to run more shifts to get your throughput.

Lower Labor: You want to have a lower headcount. This is the focus on your more advanced DC’s. Technology takes the place of an army of people on forklifts. Product-to-person picking is an option here.

Effect on Capital: There is a bigger expenditure of capital in the beginning. However, there are immediate returns in accuracy and labor savings though.

Effect on Space: With advanced technology there is usually a smaller footprint. This means that you can buy more desirable land closer to your outlets or the transportation trunk.

Less Space: You want to use the least space. The easiest way to do this is to just run more shifts in your smaller DC. You can run into problems though if you require a lot of storage.

Effect on Labor: This can go two ways. If you have less technology you will need a lot of labor in your smaller footprint. Technology can use the air above the floor much more effectively, so you can have less labor.

Effect on Capital: This is the same as the effect on Labor for the smaller footprint. If you want to save on capital and have a small footprint you will have a lot of labor (shifts). If you go the other way and want more storage and a smaller footprint you will have to invest more capital.

The trick is getting the balance right for the ROI you are trying to achieve.

So what does all this mean when you are choosing a supply chain partner? Most engineering firms use the one-size-fits-all philosophy – they try to manage the whole warehouse with a single type of technology (pick-to-light or pick-to-voice).

And unfortunately that technology will dictate what your capital, labor and space will be. One size does not fit all.

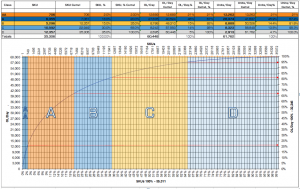

Different technologies have a different impact on ROI depending on where you are on the Pareto curve. It doesn’t matter if you are picking a pill or a pallet, economics of automation change as you move to the right on the Pareto curve.

Be sure that you pick a partner that can design the right technology for each bandwidth of your individual curve. Just like people, no two operations are alike; they are as distinctive as your fingerprints.

This will ensure that your decision of how you allocate your footprint, labor and capital.

Want to know more about how to help you “tame the curve”? Download our White Paper on New Trends in Distribution.

How to Use Automated Distribution for “Museum Pieces”

In previous blogs , I have reviewed the Pareto Principle, or the 80-20 Rule, and of the trap of a single-technology system for the entire SKU base. I have also talked about fast-moving SKUs and how to deal with them from a technology standpoint.

In this post, I want to go to the opposite end of the Pareto curve to the C- & D-movers. I like to refer to these as the Museum Pieces because they often sit in your distribution center and generate no business. If you walk through your distribution center they are usually easy to identify; they’re the ones covered in dust.

MUSEUM PIECES

I went through a liquor distribution center last year where they slotted SKUs by product velocity. As I passed through the carton flow racks – the A-, or fast-movers, I saw some SKUs that had been there a long time. These were obviously SKUs that were once slotted as fast-movers, but had long since died in demand. Lesson learned: the Museum Pieces can show up anywhere, and you have to be aggressive in identifying them and moving them to the appropriate pick zone. This is where technology really helps – by automatically identifying and re-slotting these SKUs.

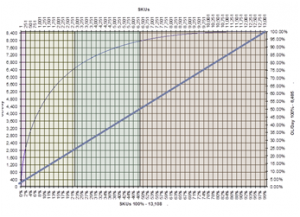

Now let’s look at the Pareto curve. Obviously, the Museum pieces lie to the right end. But how far to the left can we go before we are including SKUs that move too fast? The answer lies in the technology we will use for selecting these items.

P2P TECHNOLOGIES

There are a lot of technologies out there that serve this area of the Pareto Curve, all based upon the product-to-person ideology. Rather than sending a selector to the warehouse to identify and select an item, these systems use technology to bring the product to the selector. We call this product-to-person, P2P or goods to man .

Many companies claim that they can generate 1000 order-lines per hour and while it is true that many of these systems can deliver 1000 totes of product to a work station for picking, it is not true that a human being can sustain this pick rate over an eight-hour shift. A good planning rate for these systems is 650-700 lines per hour. Note, however, that this rate is double the effective rate of pick-to-light or pick-to-voice.

DESIGNING WITH P2P

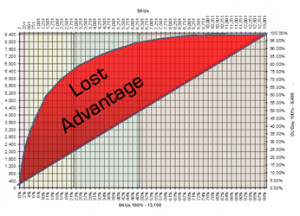

Armed, now, with a pick rate of 700 OL/hr, let’s consider the Pareto curve above. The curve above shows order-lines (OL) per day on the Y axis, and SKUs (in percentage and numbers along the X axis. So if we had a system that would generate 700 OL/hr for a single shift, it would do 5,600 OL per shift or 5,250 if we include two 15 minute breaks.

If we used two systems instead of just one, we could handle 10,440 OL/shift. Now if we consider the Pareto curve, we can see that the operation requires we do about 60,000 OL/day. Beginning from the top of the Y axis, we subtract 10,440 OL/day, and we arrive at 49,560 OL/day, or roughly 50,000 OL. Look where this point falls on the Pareto Curve; right at the boundary of the B- and C-movers. So with two systems, you can handle all of the C- and D-movers with two full-time employees who will generate about 10,440 OL/day.

Alternatively, you could have a single system that would manage this volume over two shifts instead of one. You still need two FTEs to process the work, but only need to spend half the capital to do the job. This is the benefit of product-to-person systems. This system manages 65% of your SKUs, 20% of your order-lines with only two people.

These systems are extremely effective for managing your Museum Pieces.

CUBIC VELOCITY

One more concept we need to consider in applying these systems is cubic velocity. Let’s consider for a moment two common items; coffee cups and No. 2 pencils. Both of these items move at 24 OL/day, and both have an average of 1 piece/OL. That means on an average day, we will move a tote 24 times to the pick station and each time we will pick 1 coffee cup, or 1 pencil.

Now, if I can only fit 24 coffee cups into a tote, it is plain to see that at the end of the day, I will have exhausted the supply in the tote, whereas in the pencil tote, I would hardly notice 24 pencils missing. Clearly, cubic velocity has both replenishment and storage implications. I will have to replenish the coffee cups much more frequently than the pencils that will create movements in my system.

This creates what I affectionately call “thrash” in the system. These products are better placed in a flow-rack channel or a pick location where I can replenish multiple cases at once.

This leads us to the second point – storage. Yes, you could have multiple totes of the same product in the P2P technology, but the cost of the multiple locations in this technology argues against it. Again, a simpler storage location where more of the same product is stored might be more effective.

Coffee cups would work well in a flow rack location, where pencils would be ideal in the P2P system. In selecting SKUs for the P2P technology, then, the product velocity AND cubic velocity must be considered.

Later we will focus on what to do with all that remains – the leftovers. I would be interested to hear some examples of how your company concentrated your slow-movers and dealt with the Museum Pieces. Do you have a clever use of technology to solve this problem? Let us know by commenting below!

An Efficient Distribution Center from Pulling the Weeds

In my last post, I talked about the Pareto Principle, or the 80-20 Rule, and of falling into the trap of a single-technology system for the entire SKU base. In this installment, I want to talk about the fast-moving SKUs and how dealing with them can make your distribution center more efficient.

The fastest-moving SKUs in the distribution center are the top 20% of the SKU base. These SKUs generate, around 80% of your volume.

Now, the ratio of 80-20 is not always exact; nor is it proportional to 100%. For example, some companies have an 80-30 relationship meaning that 80% of their volume is generated by 30% of their SKUs.

That’s OK.

It just means that the slope of the curve for your operation is not quite as steep as Mr. Pareto would suggest. What is important is that you identify the group of SKUs that do generate 80% of your volume, and focus on these. These make you money!

The principle of efficiency is to concentrate the fast-moving, frequently-touched SKUs in single area. “Pull the weeds” – eliminate all other slower–moving SKUs, so you can efficiently service the 20% of your product base that generates 80% of your volume. By pulling the weeds, you can make even more money because you will generate business with less effort.

Now, the top 20% really has two sub-sets: the top 2% (AA-movers), and the next 18% (A-movers).

The top 2% have wings. They practically fly out of the distribution center by themselves. If you run a distribution center, you know right now which these products are in your gut. Your employees all talk about them.

Remember when the iPod Nano® came out? The cartons practically came with retro rockets to move them faster through the supply chain. Distribution centers couldn’t keep them in stock.

And that’s the problem with these SKUs; replenishment. The most difficult part of managing these SKUs is not picking them – you can do that with snow shovels. The difficulty is keeping up with the replenishment tasks.

When you think about technologies for the top 2%, think in terms of replenishment. How do I replenish the pick location with as little movement as possible?

Specific technologies will vary, of course, upon the SKU or carton size. The principle is to replenish the largest unit practicable. In full-case picking, the replenishment unit is always a unit-load, or pallet.

When the Nano came out, we were suggesting this product be replenished by the pallet-load as well. The picking was done by a pick-to-light display over a set of pallet locations for the AA movers. Think about it; if you were to replenish those Nanos at the case-level, how many man-hours per day would you spend replenishing the pick slot? You would be back every 15 minutes with more cases. For the AA-movers, tackle the replenishment tasks first.

The next 15% — the A movers — require that you “pull the weeds.”

Think about how many products your selectors have to walk past to get to the products they need to fill an order. If 80% of your volume is done by the top 20%, it stands to reason that you need to get the other SKUs out of the way.

Now that you have this 18% concentrated in one area, what can you do?

Technologies to consider:

Automated picking systems (A-frames) – these systems automatically pick the order for you. They can generate as much as 2,400 32-piece orders per hour! The drawback of A-frames is that they are form-factor specific; they require small, lightweight cuboid-shaped or stackable products.

They are ideal for pharmaceuticals, cosmetics and office supplies. They are off the table for apparel, poly-bagged items or irregular shapes. There are automated machines for all three bandwidths of the Pareto curve, so if you have these types of products, they are something to consider.

Mini-load-replenished put-to-light or batch-picking systems – most people are well-familiar with pick-to-light technology. The following application may also be done with pick-to-voice. The new twist here is to glue the pick-to-light locations onto the side (the long, down-aisle side) of a mini-load. What you have now is an automatically-replenished pick-to-light location.

What is so special about this?

You get the picking efficiency of pick-to-light (250 lines/hr +) and no people required for replenishment. All of the replenishment stock is in the air above your head (nobody can get to it to cause shrinkage or inventory changes), and the control system tells the mini-load crane when to bring down more stock. But wait! That’s not all! You can also use the crane to swap out SKUs no longer needed during the picking shift to condense your pick zone even further. (Be careful – this must be carefully engineered – do not try this at home!)

Pick-to-light with zone-bypass conveyor systems – This technique embeds the conveyor system into the flow-rack and consists of two conveyors: a transport conveyor (the highway), and the picking spur. The transport conveyor is closer to the back of the rack, and the picking spur is on the pick-aisle. This arrangement allows the conveyor system to bypass pick zones the order tote does not need to visit, and only visit the ones it needs.

This is, of course, not an exhaustive list, but merely some examples to get the juices flowing. I would be interested to hear some examples of how your company concentrated your A-movers and pulled the weeds. Have a clever use of technology to solve this problem? Let us know! Learn more about new ideas in distribution; Download abco AUTOMATION’s whitepaper!

Expanding the Pareto Principle in Distribution

Only 20% of the SKUs in your distribution center make up 80% of your volume.

This point, to most people in distribution, is not a big surprise. Most people already know the 80-20 rule, or at least have heard of it. What is a surprise to most people in distrib ution is that they are missing huge opportunities in efficiency by not applying the rule. As a systems integrator I see different distribution centers every week. No matter what industry I go to – from apparel to auto parts – everybody does distribution the same basic way. Oh, there are nuances, of course, but by and large, they use the same application of technology for their entire operation. They ignore the Pareto Principle.

ution is that they are missing huge opportunities in efficiency by not applying the rule. As a systems integrator I see different distribution centers every week. No matter what industry I go to – from apparel to auto parts – everybody does distribution the same basic way. Oh, there are nuances, of course, but by and large, they use the same application of technology for their entire operation. They ignore the Pareto Principle.

Let me explain.

Italian economist Vilfredo Pareto observed in 1906 that 80% of the land in Italy was owned by only 20% of the population. Later, business-management thinker, Joseph M. Juran, further developed the 80-20 rule and named it after Pareto by observing that 20% of the pea pods in his garden contained 80% of the peas.

In the distribution center, like the garden, the same principal holds true (in general).

Balance is not always good. Leveraging the natural imbalance of product movement is an opportunity to drive tremendous benefits to you and your company. Single-technology distribution systems assume that all products should be handled the same way. Think about it – if you have a static pick slot for every SKU in your distribution center, and you have a person walk to every location, you have a single-technology system. Single-technology systems make the assumption in the chart on the right.

Mr. Pareto would suggest that we should apply different technologies on the 20% of the SKUs that generate 80% of your business than we do on the 80% of the SKUs that only generate 20% of your business. In other words, we need to apply multiple technologies to optimize the efficiency in different “bandwidths” of the Pareto Curve of your SKU base.

Get this principle right and you are well on the way of creating a world-class distribution operation.

In subsequent posts, I will talk about what technologies apply to different parts of the Pareto curve, and why. Stay tuned!

Want to learn more about leveraging the Pareto Principle in your distribution center? Contact abco automation for a consultation.

abco automation Partners with Dematic North America

abco automation, an integrator of distribution solutions, announces the addition of Dematic as a strategic partner. Dematic, a provider or warehouse logistics automation technology, will provide key components for the warehouse solutions offered by abco.

When asked about the abco automation and Dematic partnership, Cory Flemings, VP of Sales for abco automation said, “abco automation is not just another systems integration house; we bring specialized product-to-person expertise steeped in over 10 years of working with European systems integrators. Partnering with Dematic will allow us to do this in our time zone, in English and with an American supplier who can supply spare parts right out of Kentucky. We bring the efficiency of European distribution concepts to American-built technologies.”

“abco automation doesn’t believe that one technology fits all SKUs. Working with the Pareto Curve, we apply different technologies to different product velocities which yields ‘more bang for your distribution buck.’ Most system integrators use a one-technology-fits-all philosophy which doesn’t take advantage of the natural imbalances that exist within SKU movement.

“Without a strong technology partner like Dematic, we couldn’t do what we do. abco automation is extremely pleased that we have been selected to be a Dematic partner; there isn’t another partner out there who can offer what Dematic does.” Flemings said.

When asked about the relationship, Steven Buccella, VP Corporate Sales and Business Development said, “We believe our partnership will be mutually advantageous. We both bring something unique to the partnership and are very excited about the future synergy between Dematic and abco automation.”

###

About abco automation – abco automation is an American firm specializing in the design and implementation of American-built, capital-efficient distribution systems. We are a straight-speaking, flexible, fun-to-work-with, American company that designs and installs product-to-person (P2Psm) picking systems at a fair price. We specialize in identifying and applying the right technology for fast-, medium- and slow-moving products. All of abco automation’s designs rely on looking at the customer’s solution through the lens of the Pareto Curve. abco automation designs capital-efficient systems that do more, in less space, with fewer people.

Please visit abcoAUTOMATION.us for more information.

About Dematic Corp. – Dematic designs, implements & life cycle supports logistics systems for the factory, warehouse, & distribution center. Engineered systems are built around process improvements, automated material handling technologies, and software. Typical solutions optimize logistics performance by reducing building space requirements, fulfillment time, and labor to operate while increasing throughput, accuracy, and ergonomics.

Dematic is a global company with operations in 22 countries. North American presence includes an engineering/manufacturing headquarters in Grand Rapids, Michigan, and 18 sales/engineering/service offices. Prior to adopting the Dematic name, the company was known as Rapistan. For more Dematic information, visit www.dematic.us.